As I started to really dive into SvelteKit, I couldn’t help but find myself drawn to this idea of writing as little code as possible. Don’t get me wrong — I still love working with C#, and honestly it’s still where I’d turn to in a heartbeat if I had need to model a complex business domain.

I haven’t been able to shake the thought though, that quite often we end up building rather small applications that might be simpler and faster to write using one of the current full-stack meta-frameworks. While SvelteKit has been my poison of choice in that regard, what is outlined here is framework-agnostic and should be applicable to any of the current offerings.

ORMs, script builders, raw SQL…

I have to admit to feeling a little lost when I first stepped into the idea of managing persistence without my trusty Entity Framework Core. Instinctively, I reached for an ORM and did some poking around.

I came across this fantastic post outlining the usage of Drizzle. I was pretty excited, things looked nice and easy to implement. Getting started was fairly straightforward using a Postgres database, but as I looked around I started stumbling across discussions such as this one outlining the shortcomings of Drizzle.

Nice as it was, I decided to keep looking.

TypeORM looked like a long term player, but seemed to be an unpopular choice.

Prisma looked a bit more positive, but I mistook their “pricing” page to indicate it was a paid option, which I later discovered was not the case, however the ship had sailed by this point.

MikroORM received the most praise based on my research, but wasn’t quite as easy to get set up as Drizzle.

By this point I was pretty over the idea of using an ORM in TypeScript-land.

Or something else…?

I have to credit this post on Reddit for pointing me in the direction I eventually found myself going in.

While the post itself goes into using GraphQL which isn’t something I was particularly interested in, it did cause me to start looking into what a solution might look like if it were truly data-driven — allowing your database to be the source of truth for your application.

This resonated with me, as someone who typically preferred a data-first approach. It aligned very closely to my typical workflow in .NET where I’d use DbUp to handle database migrations.

The magic sauce

After a bit of a dig at just writing plain SQL, I decided to finally give Kysely a crack — a simple, no-nonsense query builder for TypeScript. It had consistently received high praise wherever I had seen it mentioned, and suffice to say I was not disappointed when I finally used it.

But first, we need some data!

graphile-migrate

The aforementioned Reddit post eventually landed me on graphile-migrate — a migration tool that introduced an interesting way to manage migrations.

While I can certainly envision some scenarios that could get a little messy, the premise is that you would write your migrations to be idempotent. Writing your migrations to a current.sql file would allow you to use the tool’s watch mode, re-running the migration every time the file is changed.

Once work on the “current” migration is complete it can be committed, which will move it into the committed folder as a migration ready to be run against a production database.

Despite needing some additional thought to how best to write idempotent migrations, I found that in practice it allowed for a much more iterative workflow when compared to the usual sitting down and figuring out all of the data requirements as the very first step.

We’ll use the following migration to illustrate how the other tools are used in a basic real-world scenario.

| |

kysely-codegen

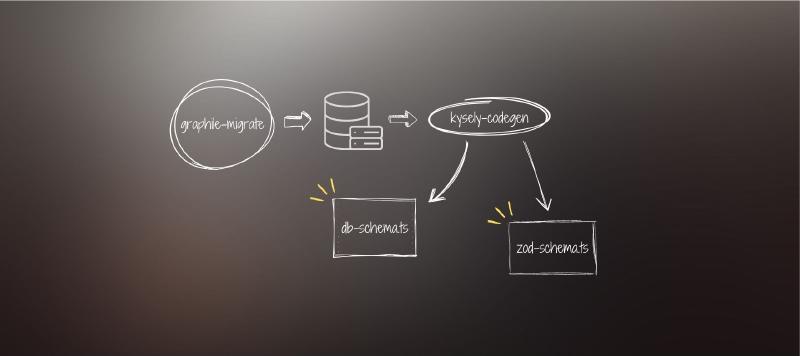

Before we can work with Kysely, we need to provide a database schema in a format that Kysely can understand. Database introspection isn’t something I’d done much of, and fortunately the Kysely documentation outlines a few tools that can aid with this.

kysely-codegen as one of their offering purports to work with all dialects supported by Kysely itself, so that was the one that I picked off the list.

Configuration for graphile-migrate allows for running commands at various points, such as after all migrations, or after just the current migration. This allowed for a simple way to run kysely-codegen every time graphile-migrate’s watch function caused the migrations to re-run. Nice!

Running kysely-codegen against the database after the migration above was applied yields the following.

| |

kysely

I can’t stress just how impressed I am with Kysely despite not having worked with it for long. It really does a fantastic job of not trying to do too much — it just gets out of the way and makes it feel quick and easy to work with.

Setting up the database client using Kysely was very straightforward.

| |

I decided to break the tables down into repositories for ease of access, and here we can see how simple queries look using Kysely. We get full type-safety along with auto-complete while writing the entire query, and I found that the query itself mapped nicely to what I’d expect the generated SQL to look like.

| |

Kysely provides us with Selectable<T>, Insertable<T> and Updateable<T> wrappers for each table, which should give us the correct types for each respective operation.

Additionally, you can replace execute() with compile() or explain() to get an idea of what’s being generated under the hood. See the following for a truncated example based on running compile() against the create(...) command above.

| |

Going even further

I was pretty happy with what I had landed on here, but I started wondering if we might be able to also extract some additional metadata and generate validation schema based on some of the database properties — namely wherever we’ve used varchar(n).

Yeah, as you can probably tell I’ve run into a few cases where our application’s validation hasn’t been updated to reflect a change in the database schema. I wanted to try and fix that.

I started out here looking around at various options, including replacing kysely-codegen with kanel-kysely just so I could leverage kanel-zod for this purpose. I was left underwhelmed at what was actually generated, and decided to go back to the drawing board.

Generating Zod validation schema with kysely-codegen

The 0.18.0 release of kysely-codegen introduced the ability to define custom serializers, largely related to this GitHub discussion. This gave me most of what I was after once I’d extended the example provided in the linked release notes to include more extensive mappings.

Something that appeared to be missing yet as one of the key reasons I wanted to look into database-driven Zod schema was the ability to extract maximum character lengths for varchar columns. Of course, there is advice floating around that suggests preferring text instead of varchar, but it’s a habit I can’t shake.

I also wanted to refrain from mapping check constraints — I needed to draw a line here and stopping short of check constraints felt like a good balance between simplicity and functionality. So, consider that to be a caveat of this approach, although nothing is stopping you from extending the serializer to account for check constraints either.

Scripts

I eventually settled on adding the following script to allow me to grab additional metadata from the database, essentially returning a mapping between column names and their character_maximum_length property.

| |

Configuration

I’ve truncated the mapDataTypeToZodString(...) function below for brevity, but it retains all the mappings required for the tables defined so far.

| |

Output

| |

Usage

Now that we have our Zod validation schemas, we can use them for form validation. In the case of a create player form we only ask the user to supply three of the properties, so we just restrict the schema accordingly.

Once that’s done we can extend the schema to add rules to an individual property. This allows us to layer business rules on top of our database-driven validation.

| |

In this case, changing player.image_url from varchar(2048) to varchar(20) would cause the form’s validation to instantly reflect that change without needing us to go and modify a separate schema.

Conclusion

After digging through a swathe of options when it comes to managing persistence in a full-stack meta-framework, eventually stumbling upon the above felt like a revelation.

While no doubt there will be hitches along the way, this presents a way to move forward quickly and iteratively with data changes, allowing them to propagate throughout your codebase via the generated types.

Essentially, this boils down to a very straightforward workflow — add a migration, let it spin for a second or two, and start using the generated types.